In Flight: British Modernist Printmaking's Ongoing Renaissance

A new exhibition in London puts the spotlight back on the Grosvenor School linocut printmakers. Here’s everything you need to know about a genre whose market “went from 2 guineas to £100,000"

Adam Heardman / MutualArt

Jun 27, 2019

A new exhibition at London’s Dulwich Picture Gallery puts the spotlight back on the Grosvenor School linocut printmakers. Here’s everything you need to know about a genre whose market “went from 2 guineas to £100,000.”

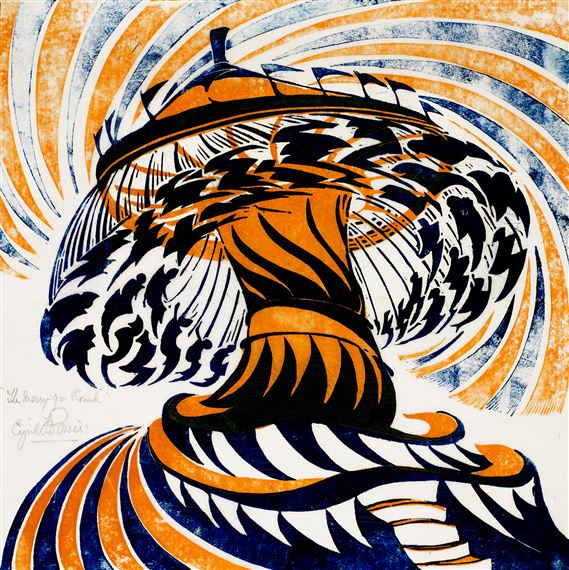

Cyril Power, The Merry-Go-Round, c.1930, © The Estate of Cyril Power. All Rights Reserved,[2019] / Bridgeman Images/ photo The Wolfsonian–Florida International University

For a movement whose lofty ambition was matched only by its fleeting lifespan, there can be no better-named leader than Claude Flight. His apt surname also conjures the physical sensations of motion, dynamism, speed, which were so well communicated by the practitioners of Flight’s beloved linocut print techniques. The story of the Grosvenor School and its group of exceptionally talented and idealistic printmakers is the story of interwar Britain and America. Their socially progressive agenda, their cogent political optimism, and the boom and bust cycles of their artistic reputation and financial value move alongside the complex rhythms of Europe and America between the two World Wars.

Cyril Power, The Tube Station, c.1932, Photo Osborne Samuel Gallery, London/ © The Estateof Cyril Power. All Rights Reserved, [2019] / Bridgeman Image

Flight had a vision of “an art for the people, for their homes.” He wanted linocut prints in every kitchen or living room, high art rendered through cheap material processes bringing expressive creativity into the lives of everyday laborers. He wanted linocut lending libraries, exhibitions in cinemas, and a public making their own prints. Though this vision never quite reached fruition, the intense period during which Flight’s influence spread can be seen in hindsight as a high watermark for socially minded art in Britain.

The artists who worked under Flight’s tutelage at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art from 1925 onwards include Cyril Power, Sybil Andrews, Lill Tschudi, and prominent Australian printmakers Dorrit Black, Ethel Spowers, and Eveline Syme. Each developed in their own ways the particular materiality of lino-printing to depict the activity of the jazz age, the intersection of leisure and labor, and the optimism of everyday life in the maturing 20th century.

The Dulwich Picture Gallery this summer presents Cutting Edge: Modernist British Printmaking, an extensive selection of 120 prints, drawings, and posters from the era, celebrating 90 years since the Redfern Gallery in London held the first exhibition on British linocuts.

Installation view, Cutting Edge: Modernist British Printmaking at the Dulwich Picture Gallery

Influences on the Grosvenor School are highlighted at the beginning of the exhibition. Of course, the bleak vistas of Paul Nash’s warscapes, their monochromes and their geometries, are a powerful precedent, as are the advances in the expressive use of color made by David Bomberg. Italian Futurism and the gathering pace of Vorticism in Britain were important contributors to the aesthetic sensibilities of the new mechanical age of Modernism at large. But, as the exhibition makes clear, the driving force behind this brief but bright moment in modern British art-history is Claude Flight’s “dearly held ambitions for the linocut to become the medium to empower the general public to appreciate, own and practise art themselves.”

These are the words of Hana Leaper in the exhibition catalogue. Another contributor to the book is gallerist, collector, and curator of this exhibition, Gordon Samuel, who asks the pertinent question, “So how did the market for these linocuts go from 2 guineas in the late 1920s to over £100,000 by 2010?”

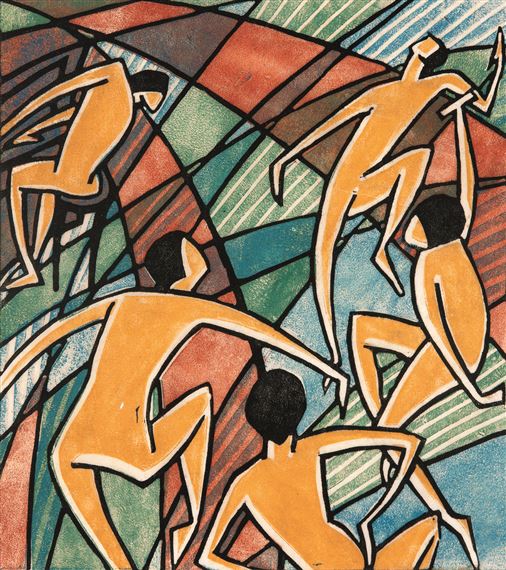

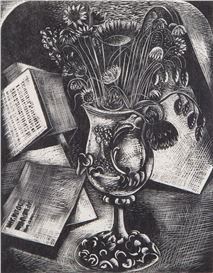

DorritBlack, Music, 1927-28, Elder Bequest Fund1976, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaid

With Claude Flight’s help, the Redfern exhibition took to the skies. As Samuel highlights, the complete 1929 exhibition was flown to America “and has been, and still is being, exhibited there with continued success.” Other collections toured Britain, and were exhibited with great frequency. On its visit to the North East town of Sunderland, a working place of shipbuilders and coal-miners, an early 1930s exhibition of British linocuts attracted as many as 12,000 visitors.

The British and American publics of the interwar period found in these linocut prints the perfect symbolic language of their age. The clean but jangling motion lines in, for example, Dorrit Black’s Music (1928) communicate the fervent atmosphere of the jazz age, the figures - seemingly unclothed, undeniably joyous, transported into attitudes of terpsichorean freedom and grace - act as archetypes of a generation beginning to be defined by self-expression.

Similarly, Cyril Power’s The Merry-Go-Round (c.1930) and Speed Trial (c.1932), as well as Sybil Andrews’ The Windmill (1933) are effervescent with motion.

Sybil Andrews, Concert Hall, 1929, © The Estate of Sybil Andrews/ photo Osborne SamuelGallery, London

Though less insistent upon speed and movement, Andrews’ Concert Hall (1929) offers a clue to the infectious optimism which is scored into the lines of these works. As new labor laws were introduced between the wars, ordinary people found themselves with shorter working days. Evenings were free for new and exciting forms of recreation. The rows of rapt faces in Andrews’ picture, hushed as the lights dim and the show begins, represent a new working class engaged with the arts and in greater control of their self-actualization. The swooping shapes of the hall’s architecture are a thrilling exercise in line-making. The space must have felt to these new audiences like a zone of discovery. Like many of the prints in the exhibition, Concert Hall frames its subject matter in a dramatic orchestration of linear perspective - a literal comment on the changing social and political perspectives of the age.

Sybil Andrews, Speedway, 1934, Photo Osborne Samuel, London/ © The Estate of SybilAndrew

The inherent tension between geometry and motion in linocut printing lent itself to depictions of both recreational sport and labor. The subject matter, the symbolic resonance of the cheap materials, and the mechanics of the process, meant that linocut began to flourish as the art of the age.

Despite this, the ‘2 guineas’ price that Samuel highlights was still far beyond the means of the average working Briton. Still out of reach for the working populace to whom it addressed itself, and considered ‘low’ art by many institutions and collectors, the linocut print fell out of fashion, and remained a seldom-cited footnote in art history for many decades.

Its rediscovery is owed in no small part to Michael Parkin. As his 2014 obituary in The Guardian states, "Almost single-handedly he rediscovered the work of the Grosvenor School of linocut artists from the 1930s, led by Claude Flight, which was unseen for 40 years and now enjoys widespread critical and commercial acclaim.”

Parkin’s colorful reputation and gregarious personality meant his influence spread wide. He infamously worked with the UK’s first pirate radio station, broadcasting from a boat in international waters. From his gallery in Halkin Arcade, and with the help of collectors like Samuel himself, he oversaw the Renaissance of British prints. Samuel marks the watershed moment in 2012 when a copy of Sybil Andrews’ Speedway (1934) sold at auction for £82,850.

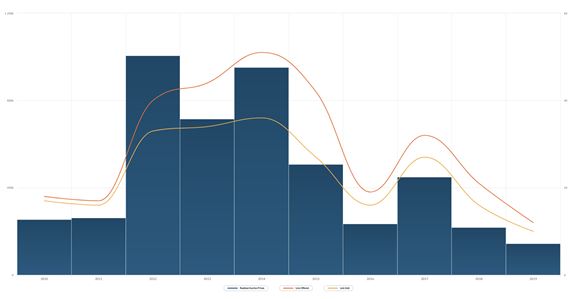

Graph showing total sales value by year alongside number of lots offered and sold for Sybil Andrews

MutualArt data shows the robust health of Andrews’ market over the last decade. Though the boom of the early 2010s seems to have passed in terms of total sales value, this can be explained by the far greater number of works which came to market in the years from 2012 to 2014. There is a strong correlation between works offered and works sold - when an Andrews print comes to market, it sells. The total sales value rises in line with the number of works sold, indicating strong performances when her prints do come to auction.

Installation view, Cutting Edge: Modernist British Printmaking at the Dulwich Picture Gallery

Though Flight’s “social vision of a linocut in every home, affordable to an ordinary working man or woman” proved unattainable, this new exhibition, and the dissemination of these works through an active market, is helping to give British printmaking a currency and a relevance which endures.

Cutting Edge: Modernist British Printmaking runs from June 19th until September 8th, 2019.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Articles Page

ARTISTS

ARTISTS